The Short stocky man sits at a table at the back of the bar. He is balding, paunchy, has bushy dark eyebrows and sports a similarly bushy moustache which is white/grey in colour in contrast to the eyebrows.

He will tell you that he sports the moustache in honour of his father and that he feels naked without it.

Regular processions of people come to the table to shake his hand, kiss his forehead and just get a few words from him. It is a scene befitting of an Italian Godfather as portrayed by Hollywood, and in this instance it is totally appropriate as the man is indeed of Italian ancestry.

At one point, he gets up from his seat, and opens a cage within which a bird of some kind has been squawking. He takes the bird out of the cage, caresses it, talks to it, feeds it, and gently places it back in the cage. He has a fondness for, and an expertise in, birds it seems. Particularly those of the parrot and finch variety.

The man is clearly at home. When he smiles he does so with charismatically wrinkled eyes. He is engaging, constantly laughing and very descriptive in his stories – and he has plenty of stories!

He was born on the first of January 1946.

The first day of the year is said to be the day when the happiest and luckiest people are born and the paunchy man certainly considers himself to have been lucky and he most definitely appears happy with his lot.

He is always ready with a joke and a funny story.

He describes how a former boss once suddenly chased after a professional colleague whilst waving a gun about with the intention of shooting him. This act of potential violence in turn led to the boss man being replaced. “That was lucky for me & things really changed for me then!” he says with a smile and without further explanation.

However, that incident is part way through his story and to understand this man’s unique journey, and indeed his legacy, you have to go back to the start.

Ever since he could remember, the paunchy man loved to play football.

He would play in the city streets with no socks, no shoes and no ball. He and others played with anything that resembled a ball, and they would play till their feet bled, even though they were wrapped in bandages and covered in skin which was as tough as old leather.

From rough unorganised games in the streets, he progressed to indoor football. Five a side games or futsal as it was known locally.

Eventually he would get to play on the big pitch with a full blown eleven a side team. However, it was on the street, and later in those futsal games, where he learned to control a football and move it along with an extraordinary degree of skill, and in ways which the world of football had not seen before.

By the time he was sixteen he was playing for a local team which reached a state final against the youth team from the club that he and his family had always supported and had always adored. It was his dream to play for this club, but on this day and in this match he would do everything he could to defeat them. It was the biggest game of his life.

In the final he played well, really well. In fact he played so well that he caught the eye of the management team of his boyhood heroes who saw a stocky youth, with supreme confidence, unbelievable skills and what appeared to be a magical left foot.

After the game he received a call from one of the club’s directors asking if he would be interested in playing a trial for the club. He accepted at once and was delighted to start training with the club he had always dreamed of playing for.

However, his luck did not hold, and before the third day of his trial, he was told by the club’s coach, Mario Travaglini, that he would not be receiving an offer from the club. He was invited to stay and train if he wanted, but there would be no contract at the end of the sessions.

The young man was angry and declined the offer there and then. He walked out on the club he loved but vowed to forge a career in football – somewhere. Shortly afterwards, he turned up at the gates of the great rivals of the club he and his family had always supported and once again played in trials and impressed.

This time his impressive performances caught the eye of a coach who thought the boy was good enough to take a gamble on. Sure, the player was not the tallest, he would never stand above 5’7”, but he was strong, confident, had an abundance of ability, a fierce shot and that magic left foot.

“What’s your name, son?”

“My name is Roberto – Roberto Rivellino — with two L’s”

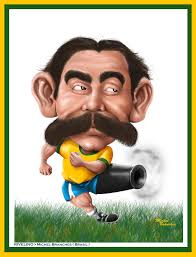

For those of a certain era, the very name Roberto Rivellino conjures up a mental image of the short, stocky, tousled haired Brazilian player with the fierce left foot shot and the wildest, craziest, bushiest moustache in the history of football.

And so it should, because Rivellino was a one off visually. No other football player before or since had his look and swagger, nor his crazy arm waving celebrations when he scored a goal. Almost 50 years on since the magic Brazilian played in his pomp, you will find kids in his native Sao Paulo, who were not born when he played, mimicking his style, donning false moustaches, wearing Rivellino wigs and masks, and acting out the manic arm movements he used to celebrate the ball hitting the back of the net.

Almost 50 years on and those who were not born when he played are mimicking him – both on and off the park.

Rivellino was a truly unique talent, and it might surprise some to learn that his impact on the game of football is still very evident, if not actually increasing, to this day. To gauge just how highly “Riva” is regarded you have to listen to the words of those who played with him and against him—and maybe one or two others!

The boyhood club that rejected him was Palmeiras (much to their later regret) and it would be with their great rivals, Corinthians, that “Riva” would make his name and first display his skills.

Having joined the Corinthians’ youth ranks he made his debut with the senior team aged just 18 in 1964 and very quickly he established himself as an absolute favourite with the crowds. In the end he would make 471 appearances for Corinthians over a 9 year period.

Of course, when Rivellino started playing professional football, Brazil were the World Champions having won the Jules Rimet trophy in 1958 and again in 1962.

Amazingly he made his International debut within a year of playing in his first full professional football match forcing his way into a glittering international squad before his 20th Birthday on 21st November 1965. By the time the 1966 World Cup came round he was in and around the group being considered for the trip to England.

However, the then national manager, Vicente Feola, who had led Brazil to success in the World Cup Finals of 1958, decided to leave the young Rivellino out of the final squad which would travel to Europe.

There was no doubt that Feola recognised and appreciated Rivellino’s talent, but the moustachioed player wore the number 10 shirt for his club, was barely out of his teens and well …………. Brazil already had a stocky number 10 called …….. Pele.

Accordingly, the youngster with the mop of hair and the moustache stayed at home while his countrymen jetted off in an attempt to secure their third successive Word Cup.

Of course, it was not to be and Brazil underperformed in England even although their squad boasted many names which would become not only familiar but legendary in the game of Football.

In addition to Pele, the Brazil squad of 1966 boasted Tostao, Gerson, Piazza, Jarzinho, and Brito who were all lined up alongside names such as Garrincha, Djalma Santos, Bellini, Lima and others.

Despite having players like these, Brazil failed to progress beyond the group stages losing 3-1 to Hungary and by the same score to a very physical Portuguese team who boasted the star of the Tournament one Eusébio da Silva Ferreira.

The Brazilian press and public turned on the team that had promised so much and for the next few years that public remained sceptical and critical of the national side and the men who would manage it.

Having failed to defend the World Cup title, Feola stepped down to be replaced by a succession of new managers during a period when the national team seemed to suffer from inconsistency and turmoil off the park.

First up was the man who had taken over from Feola after the World Cup Triumph in 1958 and who lead the team to victory in 1962.

Aymoré Moreira was an unusual character in that he started his professional playing career as a right winger but eventually switched position and became a goalkeeper. He was so successful between the sticks that he became the Brazilian national keeper for an 8 year period between 1932 and 1940.

He had previously managed the National side as far back as 1953 and then again between 1961 and 1963 during which period he successfully retained the World Cup in Chile in 1962.

Accordingly when he was once again appointed as the national team boss after the 1966 World Cup it was his third spell in charge.

By the time he left the post in 1968 he had a fairly impressive record of 61 matches, with 37 wins, 9 draws and 15 losses. He not only won the world cup but various other tournaments on the South American continent as well.

Moreira’s third period in charge did not start auspiciously, especially as the talismanic Pele announced that he was no longer prepared to play International football due to the heavy tackling and rough tactics he had had to endure during the 1966 World cup finals. Pele declared he was no longer interested in representing his country and so Moreira had to rely on other players one of whom would be young Rivellino.

After little over a year in charge however, Moreira was on his way and Brazil were without a manager.

The Brazilian FA then put another goalkeeper in charge for one single game.

The new man was called Dorival Knippel but was known to everyone in Brazil as simply “Yustrich” and much later he was inadvertently to play a major part in the career of Rivellino and have an unintended impact on the fortunes of The Brazilian National team and the way it was viewed by football fans throughout the world.

However, after just that one game, Yustrich was replaced with the most political and technically surprising of appointments in the form of João Alves Jobin Saldanha who took charge of the team at the start of 1969.

Saldanha had barely been a footballer and was considered more of a journalist.

In fact, he was a very good journalist, with an engaging if occasionally crazy personality which made him very difficult to deal with. It is said that the reason he was appointed Brazil manager in the first place was because the then president of the Brazilian FA ( Joao Havelange ) hoped that by appointing a journalist to take charge of the team, the press would desist in their criticism of the FA and the players.

Crazy as it seems, that was how it came to pass that a Sports Journalist became manager of the Brazilian football team just a year before the 1970 World Cup.

For 23 year old Rivellino, the journey between Moreira and Saldanho would be a roller coaster ride of changing emotions with immense highs, and desperate lows.

Having made his international debut in late 1965, Rivellino would wait two and a half years before winning a second cap when he played in a two nil victory over Uruguay in the Copa Rio Branco.

In the intervening period he had become a stalwart of the Corinthians side and had made a reputation for himself as a skilful and explosive attacking midfielder with a brilliant left foot. He had also earned himself a nickname “O Reizinho do Parque” – The little King of the Park, with the park concerned being the name of the Corinthians home stadium, Parque Sao Jorge.

However, despite his brilliant appearances in the number 10 jersey of Corinthians, who were not a good side at the time, he found it difficult to break into the National Team which boasted a wealth of talent such as Jairzinho, Tostao, Gerson, Edu, Lima and of course the undisputed holder of the Brazil number 10 jersey – Pele.

At this stage I should explain that the No 10 jersey is revered in South America and elsewhere with the player who wears that number normally being an attacking midfielder or a slightly withdrawn forward who plays just behind the centre forward or No 9.

The No 10 is also traditionally considered to be an honour bestowed on the best player in the team. Hence the No 10 jersey being worn by the likes of Diego Maradona, Mario Kempes, Ronaldinho, Zidane, Puskas, Platini and of course Pele.

Following upon the failure of the 1966 World Cup campaign, and the retirement from International football of Pele, Rivellino got the call from the then manager Aymoré Moreira.

Having been recalled to the squad in 1968, by the end of the calendar year he had played a further 17 times in the international colours scoring 6 goals.

Official records always list him as a midfielder, not a forward, and he played in a midfield role with various players beside him and in front of him in the forward line though it was never really a settled or consistent side.

Moreira’s team won internationals against Uruguay, Poland, Mexico, Portugal, Yugoslavia, Peru and Paraguay. However, there were losses to Czechoslovakia, Mexico, and Paraguay as well as draws with Germany and Yugoslavia at home, so the progress was not startling. While the team played some nice football, the Brazilian public were far from convinced that they had a settled national side which was worthy of wearing the yellow shirt.

After his 10th game in charge, in which Brazil lost 2-1, Moreira pulled off a coupe when he persuaded the great Pele to return to the international stage and lead the forward line along with the diminutive but consistent Tostao. Until that point Moreira had experimented with other strikers such as Edu, Lima and Natal, but none of these could compare to having the threat and excitement of seeing Pele fill the number 10 shirt.

Rivellino and others had contributed key goals from midfield but the side desperately needed a striker to hit the back of the net and create in the forward area consistently, and there was none better than Pele.

Accordingly, it was on 14th July 1968 that Rivellino finally got to play in the national side along with Pele with the latter playing in his usual withdrawn forward role just behind Tostao.

Rivellino, wearing the number 8 shirt, would play the role of an attacking midfielder partnering Gerson and Piazza in the middle of the park at that time.

However, despite relative success, Moreira made way for Saldanho after just over a year, and the new man had very different ideas.

Suddenly, Rivellino found himself frozen out. In the next 13 internationals he made just one appearance and that was coming on as a substitute against Chile where it took him only a matter of moments to score in a 6-2 victory.

Saldanho’s was an altogether different regime to what Brazil had experienced before. He wanted fit players and a player for each position so that his team functioned like a machine in a strict 4-2-4 system.

He also demanded immense preparation, regular national squad training sessions, an adherence to a strict diet and absolute compliance to his playing system.

His approach seemed to be working, on the face of it!

Saldanho’s team won their first nine International matches in a row, and they ran through the qualifying section of the World cup without a single loss. Going by the stats, Brazil were in good shape.

However, if you looked behind the statistics, there was another story altogether.

The Brazil fans were not impressed with the football played by Saldanho’s side. They found it boring, rigid and methodical with little flair.

Further, his regime was becoming increasingly authoritarian with Saldanho openly warring with some of his players, the backroom staff and the Brazilian FA.

As his winning streak progressed, so he became more confident in his position and progressively more outspoken about his team, politics and Brazil in general.

Saldanho was a known communist and for political or genuine sporting reasons he refused to pick a striker by the name of Dario who was a favourite of the President of the Brazil. As the pressure to pick the player continued, Saldanho became more and more outspoken against the regime and this cast a cloud over his successful results.

Worse still, Communism was banned in Brazil and so Saldanho was known to visit other countries, such as Uruguay, and make anti-Government pronouncements while visiting before flying home again and so courted huge controversy within and outwith Brazil.

However, despite all of these idiosyncrasies, it was accepted that his team was winning and as doing well in the World Cup was a matter of national pride, he was allowed to remain in office although the football supporting public appeared to be less than convinced about the abilities of his team.

However, then the wheels came of the Saldanho bogey in the most spectacular fashion and very publicly.

Having qualified for the world cup, Saldanho began a war of attrition with his own team. He became more and more dictatorial, behaving increasingly like an egomaniac.

He laid down strict and mad orders for his team in the preparations for the forthcoming World Cup. He started to dictate when and how the players could change their girlfriends, how often they could have sex, and exactly what diet they would eat.

On the question of diet, he split the squad in two, specifying one group as “the fat boys” and was at pains to limit and dictate their food intake. Pele was included among the “fat boys” and increasingly the players felt humiliated and resentful.

Further, Saldanho then picked a war with Pele in particular saying that he was blind in one eye and questioned whether or not the great striker was up to playing for Brazil at all. Pele insisted that there was nothing wrong with his sight but it was clear that he and others were adversely affected by the strange behaviour of the manager. Saldanho then went on to express the opinion that Gerson, his midfield general, had mental issues and required guidance and counselling. His behaviour had by this time become so unbearable that his No 2 resigned in protest.

All of this was clearly evident on the field of play when a lacklustre Brazil side lost 2-0 at home to their great rivals Argentina on 4th March 1970.

Not surprisingly, there was outrage on the terracing and among the millions watching at home on TV. Further, the press were clearly moving against Saldanho who stubbornly insisted on basing his team around players from Botafogo and Santos to the exclusion of others such as Roberto Rivellino. This insistence on basing the national side on players from just two teams became a running sore and the cause of heavy criticism from sports journalists and football fans within Brazil.

His Brazil team had a chance to redeem themselves just 4 days later in a rematch against the Argentinians which was once again played in Brazil.

In the intervening 4 days, a BBC Panorama crew were allowed access to the Brazil training camp and were able to report to the world that there was major conflict within the camp and that Pele himself was on the verge of quitting the national squad altogether and this time for good.

The BBC crew were there when Brazil overturned the defeat to Argentina by winning the second match 2-1 with goals from Jairzinho and Pele. However, despite the result the play was stagnant and stilted and the partisan crowd, while pleased with the result, were far from impressed with the style and substance of an uninspired and uninspiring national side.

The BBC crew reported that the result might not be enough to quell the growing criticism of Saldanho.

And it is here that fate played a hand in the career of Roberto Rivellino who was the forgotten man of the Brazilian national side.

One of Saldanho’s open critics was his immediate predecessor Dorival Yustrich, the man who had been in charge of Brazil for just one game. By this time, Yustrich was the manager of Flamengo, one of the biggest clubs In Rio, and when Saldanho heard of Yustrich’s outspoken criticism he chose to confront him in the most outrageous of fashions. He ordered his driver into his Brazilian FA vehicle and told him to set out for the Flamengo training ground where he thought Yustrich was to be found. The driver apparently asked him why he was carrying a gun but did not succeed in persuading the national coach into rethinking his mission. Once at the training ground, Saldanho simply marched in and started looking for Yustrich while waving the gun about. Apparently he met a Flamengo player whilst walking through the building and when he was confronted by the player and asked what he was doing, he simply told the player to stay out of his way or he would shoot him! Eventually, having failed to find Dorival Yustrich, Saldanho had the gun taken from him and then left without shooting anyone. However, that march with the gun more or less sealed his fate as the national coach.

This behaviour, his open communism, the loss to Argentina, the resignation of his No 2 and the festering feud with Pele and others was too much and so the President of the Brazilian FA simply disbanded the entire National coaching squad and then set about appointing a new one without Signor Saldanho.

However, before we leave the remarkable and outspoken Saldanho it would be unfair to leave the reader with the impression that the former manager disappeared quietly into the night.

After Brazil, he never managed any other football team but went back to his chosen profession of journalist. His dry and outspoken style was a huge hit in Brazil and he went on to be a very popular if occasionally crazy and outrageous TV pundit and reporter. Amazingly he became a huge critic of the “Europeanisation” of the Brazil team and despised the team’s more tactical play in later years despite the fact that his own Brazil team had been very tactical and lacked a degree of creative flair.

A lifelong chain-smoker who effectively survived for years on one lung, Saldanho died from progressive cancer whilst in Rome covering the 1990 World Cup. He was a unique character, but there is no doubt that had he remained in charge Brazil would never have won the world cup in 1970.

For that tournament, the Brazilian FA turned to the former international winger Mario Zagallo who had won the Jules Rimet trophy as a player in 1958 and 1962. The FA had approached other managers but they all declined the job believing that Brazil had no chance in Mexico and that what they were being offered was a poisoned chalice of a job.

Eventually, Havelange was able to persuade Zagallo to take the job.

Small and bespectacled, Zagallo was immediately nicknamed “the professor” and later “The Wolf”.

Unbelievably, the new manager was given the job just a few weeks before the start of the World Cup and inherited both the good and the bad from Saldanho. The good was the meticulous preparations Saldanho had made for the tournament in Mexico. Nothing had been left to chance at the chosen Brazil training camp and everything from the training pitch to the food to the scientifically redesigned shirts (they were made to measure for each player and had special sweat absorbent collars) was organised to the nth degree.

However, the “bad” was that Saldanho had left a team which played a rigid 4-2-4, was not convincing in its execution of the chosen tactics, lacked confidence, marale and togetherness, and was viewed as having no chance whatsoever of winning the world cup.

Zagallo, in direct contrast to the philosophy of his predecessor, stated at the outset that he wanted to play the best players possible instead of the best system. He wanted the football team to be exciting, inspiring and most of all attacking. But how was he to achieve this?

For a start he dropped Wilson Piazza back into defence alongside Brito and effectively transformed a defensive midfielder into a ball carrying defender.

Next, he slightly changed the role of the talented Clodoaldo and chose to promote him from the bench to partner the clever Gerson in midfield.

Gerson was not the most physical or the most mobile of players but he was clever and demanded inclusion in the team. By pairing him with Clodoaldo, who was much more of an athlete, it allowed Gerson to be much more effective.

However, the key decision in the opinion of many was to consult the senior players in the squad about the changes to be made. Whilst undoubtedly his own man, Zagallo recognised that there was no point in having experienced players such as Pele, Carlos Alberto, Gerson, Jairzinho and others if you did not consult them and listen to their opinions.

It may surprise some to learn that to a man the senior players, when asked about what should be done to improve the effectiveness and style of the team, were unanimous in their recommendation. Individually and quite separately they all recommended that somehow, somewhere a place had to be found in the team for 24 year old Roberto Rivellino – he was that important!

It is when you listen to the testimony of players who played alongside Rivellino that you begin to grasp the quality of the footballer concerned.

The 1970 World Cup was to be the first major tournament that was televised in colour and so it seemed that the game itself was suddenly bigger and better and more exciting than it had ever been, with the worldwide footballing public being treated to not only colour pictures but replays and minute by minute analysis for the first time.

Further, for many watching in Europe this would be the first time that they had the chance to see many of the world stars including the unbelievable Brazilians, many of whom were unknown in Europe. In particular, the tousled haired guy with the moustache was a bit of a mystery as he had not featured under Saldanho and so to many outside Brazil he was unknown and so they did not know what to expect.

However, the Brazilian players themselves, and some knowledgeable others, knew that Rivellino was a truly special talent.

One of these was Franz Beckenbaur who had played against Rivellino twice in the space of a few days in 1968 when he played against Brazil for a FIFA select and later for Germany in a friendly. Even although Brazil had fielded Jairzinho, Gerson, Carlos Alberto, Pele and various other well-known players, one particular player caught Beckenbaur’s eye. Before the 1970 World Cup he was asked what he thought of Brazil and commented “Well we know they have Pele – but now we know they have Rivellino too….In 1968 I came to watch Pele, but ended up watching Rivellino” Clearly in the Kaiser’s eyes the moustachioed one was the one to watch.

Back in the Brazilian camp, the praise of Rivellino as a player was unstinting and unqualified.

Players such as Carlos Alberto, Lima, Felix and various others all speak of what Rivellino brought to the football pitch,

First, there was his unbelievable close control of the football. He could stop the ball, move it, beat a man either at pace or while seemingly walking. Carlos Alberto would later say that in terms of ball technique, his dribbling and retention of the football it was almost hard to describe fully just how skilful he was.

Second, there was his ferocious shooting power especially with the left foot. Players from Brazil all knew that Rivellino could not be given any space at all anywhere around the edge of the penalty box as he would simply find a way to unleash one of those cannon ball shots which invariably meant a goal or led to a goal as the goalkeeper would not be able to hold the ball and would spill it.

Thirdly, he was arguably the best passer of a ball in the Brazilian team of 1970 – the other contender being Gerson – and probably one of the best passers of the football in the world at that time and for years to come. There is video footage of Rivellino using that left foot almost like a sand wedge. He would ping the ball about with slice, backspin or side spin with the result that the ball would bend, float, accelerate, stop , sit up and appear at the feet of players as if by magic. He would play long passes, short passes, give and goes and intricate short one twos long before Xavi or Iniesta were even born.

Fourthly, he was strong and muscular, could tackle, fight for a fifty fifty ball and either get to or get away from an opposition player with surprising strength and pace, and despite his 5 foot 7 inches he was no shrinking violet!

Zagallo had other left sided players to choose from, all of whom were very good players indeed – Ademir da Guia, Dirceu Lopes, Paulo César Caju – but none of them were Rivellino and everyone knew it.

However, to really appreciate just how good a player Roberto Rivellino was you only have to listen to one of his greatest admirers for no more than a few minutes or a few sentences, and even then some of the comments and the nature of the observations and opinions expressed might surprise some.

When it comes to talking Rivellino there is no better person to listen to than Pele.

As mentioned above, by 1970 Pele had already quit international football but had been persuaded to return to the National squad at the age of 29.

However, after the sacking of Saldanho few in Brazil believed that the national squad would get beyond the group stages of the 1970 World Cup where they were in a group which also featured England the holders, Czechoslovakia the European Champions – who had beaten Brazil twice in recent years – and Romania who were regarded as a very good side.

However, under Zagallo, Pele and Brazil rediscovered their mojo so to speak and the great striker is only too clear as to where Roberto Rivellino featured in that transformation.

“Rivellino was simply one of the greatest midfielders ever to play for Brazil. He had incredibly skilful technique and was unbelievably skilful especially with his left foot. People said that he and I could not play together because we both played in similar positions – both wearing the number 10 – and so Zagallo decided to find a place for him out on the left and make no mistake it was the inclusion of Roberto Rivellino that made that Brazil team complete or made it whole.”

Pele goes on to talk about all the usual plaudits that one hears when talking Rivellino – his dribbling, his passing, his shooting – but then he goes on to add more:

“Rivellino also brought something else. He was an incredibly intelligent footballer. He had great vision and was very clever in seeing where other players were and was able to see where the game was going before anyone else realised.”

This is something that is echoed by Roberto Carlos: “Rivellino was very tactically astute and very clever. He was asked to perform a role by Zagallo and he was fantastic at it and was so important for us as a team”

Pele again: “He had great discipline and tactical sense. That was one of his greatest qualities.”

In short, playing Rivellino on the left was Zagallo’s stroke of genius yet in retrospect no one should have been surprised.

Zagallo himself had been a left winger and a very effective one for Brazil. He was known for both his attacking and his defensive qualities but at times was no doubt overshadowed by the immense talent of Garrincha on the right wing. Zagallo had only a fraction of Garrincha’s skill and flair but made up for it with sheer hard work and a tactical knowledge of the game. Some said that he was the luckiest Brazilian on earth to have won two world cup winners medals as a player, as he was not the most skilful Brazilian of the time, but they ignore the fact that Zagallo made teams better and more effective by way of his hard work and his tactical knowledge on the left hand side of the pitch.

In Roberto Rivellino, Zagallo had the opportunity to play a far more skilful player than he had ever been in a role which he understood perfectly.

And so it came to pass that Rivellino moved left to fit into a team which some said boasted the 5 No 10’s.

Jairzinho, Tostao, Pele, Gerson and Rivellino.

While the physical and mobile Clodoaldo protected and helped Gerson at the back of midfield, so Rivellino would use all his intelligence to dictate the shape of play on the left hand side of the field which in turn allowed Gerson lots of room to roam forward into space. When he did so, it would be Rivellino who would drop back slightly and inside to provide defensive cover or to collect the ball if it broke loose and so start an attack all over again.

Brazil had played a strict 4-2-4 under Saldanho, but with Rivellino in the team the formation easily shifted between 4-2-4, 4-3-3, 3-3-4 and even 3-2-5 on occasion.

Pele is unequivocal: “The attack line of Jairzinho, Tostao, Rivellino and me was irresistible and unstoppable. No team could deal with that”.

Yet within 18 minutes of the first game against Czechoslovakia, Brazil were a goal behind and it looked as if the doubters back home in Brazil were justified in their scepticism.

Then, in the 24th minute, Brazil were awarded a free kick on the edge of the penalty box and so the TV watching world was introduced to the fearsome left foot of Roberto Rivellino.

The resulting free kick was hit with such ferocity that the Brazilian number 11 was given a new name – “Il Patada Atómica” (The Atomic Kick) by the Mexican fans and press. The ball was struck with such force that it hit the back of the net as if fired from a rocket. The big goalkeeper, Viktor, who was absolutely sensational for the Czech’s throughout the tournament, had managed to get a hand on the ball but was unable to stop it due to the ferocious pace of the shot and was left sprawling and bewildered on the ground. As the keeper looked around him and appeared somewhat dazed, the TV cameras and the viewers throughout the world were treated to the wild arm swinging goal celebrations that were to become yet another trademark of the man with the biggest moustache in football.

From that moment onwards, the Brazilian team of the 1970 World Cup would not look back. They were simply immense.

Jairzinho would end up as top scorer and Pele would deliver moments of genius and memorable goals including his 100th goal which came in the final from a Rivellino cross. The most famous moment of the entire tournament was when the Brazilian number 10 actually didn’t score after dummying the play by ignoring the ball as it came across the penalty box at an angle, and instead ran around the advancing Romanian goal keeper only to collect the ball on the other side and just miss the far side post with a first time shot when the goal was at his mercy.

And all the while, throughout the entire tournament, rigidly sticking to the left touchline, other than when he was given the signal to roam, was Roberto Rivellino.

“Look at the number of goals we scored which were created from the left hand side?” says Pele making a point.

Even Carlos Alberto’s great goal in the final was fashioned all down the left hand side. Everyone talks about Clodoaldo weaving and jinking past 3 or 4 Italian tackles with the score at 3-1 when taking the ball out of defence. However, the big Brazilian midfielder is a man on a mission at that moment because if you look at the move again you will see that he is beating the oncoming attackers with only one intention in mind. He wants to go left!

Despite constantly moving forward when he releases the ball Clodoaldo is well within his own half and he playys a short pass to the left touchline where he finds the deep lying Rivellino.

If you watch the entire move for that goal you will see that Rivellino strikes the longest pass in the move from exactly the half way line. He bends the ball up the touchline some 25 yards taking out the entire Italian midfield with a pass that has been described as “luxurious”.

The ball lands at the feet of Jairzinho who for some inexplicable reason has abandoned his normal right wing position and has wandered to the left touchline. He starts to run with it across the pitch. The right back tries to tackle and misses, with the result that the right centre back now has to advance and the remainder of the Italian defence all move across to that side of the pitch like well-trained robots.

By the time the ball comes to Pele he already knows that Carlos Alberto is tearing up the Brazilian right and as everyone knows his simple lay off is sublime.

The Brazilian captain runs on to the ball like a steam train and thunders the ball into the back of the net!

There were no Italians there to block him; they had all gone to the Brazilian left.

According to some, including the Brazilian players, it was the presence and the ability of Rivellino that forced the game and the shape of the play left and allowed Brazil to capitalize on the space created on the right.

Rivellino himself would score three important goals in the tournament, all from outside the penalty box, but it was his tactical and technical ability mixed with his individualistic creativity and flair which really made a difference to the Brazil squad of 1970.

One of his goals came against the talented Peru side which was managed by former Brazilian legend Didi. Speaking of Rivellino, he had told his team to try and prevent him from being able to shoot at all costs.

After that first game against Czechoslovakia and before Brazil played England, Pele was asked by the press if Rivellino was going to be a world star? Repeating what he had told Zagallo before the Brazilian party had left for Mexico the great man said simply “Rivellino is a world star already!”

Hugh McIlvanney reporting from Mexico made this observation on the seemingly new discovery with the bushy moustache and atomic shot.

“The new menace that had emerged since England lost narrowly to Brazil in Rio a year previously was Rivellino. He had the handsome, moustachioed and side burned face of a playboy but his body was thickly athletic and the legs bulged with power. On the field his left foot looked dainty enough to put a match football in an eggcup but the shots when they came were intimidatingly violent.”

For the game against England, Brazil would have to play without Gerson who was injured. The England midfield at the time was considered very strong and included the legendary Bobby Charlton who was partnered by Martin Peters, Alan Ball and Alan Mullery.

With Gerson out what was Zagallo to do?

The answer was simple, he would allow Roberto Rivellino to play in his favoured role in midfield in direct opposition to Bobby Charlton and introduced Paulo Cesar on the left wing.

It turned out to be a classic match with the battle between Rivellino and Charlton being described as fascinating.

Brazil would win by a single goal from Jarzinho although England would have their chances as Brito and Piazza looked shaky at the back.

A later analysis of the game points out that Bobby Charlton was replaced after 70 minutes of duelling with Rivellino, who was clearly having the upper hand in midfield especially in the second half, and that after 10 minutes Martin Peters had ceased to be a force in the game at all. The three top rated players for Brazil in the game were Jairzinho, Pele and Rivellino.

By the time the all-conquering Brazilians lifted the Jules Rimet trophy for the third time, football as the TV spectating fan knew it had changed forever.

For a start, most of the watching public had never seen anything like a step over before and the first time it was seen around the globe on live television it was performed by Roberto Rivellino who seemed to do things at a pace that was hard to comprehend.

That was just one of his tricks.

The most often copied, however, is a move that almost bears his signature and is still being perfected and changed to this day.

Rivellino maintains that he is not the inventor of the flip flap, or the “Elastico Fantastico” as it is known but he is undoubtedly the person who singlehandedly introduced the move into International football and inspired countless numbers of others to attempt the move over the intervening decades.

Some, like Pele, were never able to master the technique at all and gave up trying. He laughs at the thought of Rivellino performing the move in training before the world cup and at his own inability to perform the manoevre. With Rivellino, however, Pele describes the ball as simply being glued to his foot.

If you are not sure of the “elastico”, just think of someone rolling their foot over the football, making it go one way but then suddenly moving it the opposite way and so wrong-footing the opposing defender.

Players such as Cristiano Ronaldo and Ronaldinho come to mind in the modern era but they only know of the move because of Rivellino.

There are various pieces of footage of Rivellino performing the trick including the 1970 world cup final where he uses it to “nutmeg” one of the Italians. At times he has performed the elastico while running and on other occasions he simply stands stock still and goads the defender like a matador with a bull. The result is that the defender jumps in and before he knows it the ball that was going one way has gone another with the moustachioed matador suddenly nowhere to be seen.

One of those who watched the world cup of 1970 and who was in absolute awe of the stocky Brazilian was a young Harry Redknapp. Writing much later about the 1970 world cup he said;

“We’d never seen anyone do the Roberto Rivellino move before! He would take the ball up to an opponent, put his foot on the inside as if to go outside him and then, at the last moment, step over it and move off in the opposite direction. We couldn’t believe what we were seeing. Defenders were going six yards the wrong way, and everyone at home was asking the same question: how did he do that? I can remember the TV panel slowing the footage down so they could study how it was done? Now everybody tries it – Ronaldinho, Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo – but Rivellino was the first to do the flip flap, ……..”

“Even footballers try to imitate the greats. I think when we reported back for training that summer, everyone was trying, secretly, to see if they could do the stepover like Rivellino. I mastered it in the end but never at the speed he managed it.”

After the 1970 World Cup final, the Italian press complained that the result in the final would have been different had Rivellino been playing for Italy. They argued that given his Italian grandparents he should have been wearing the blue of the Azzurri. However, the 24 year old went back to his native Brazil and Corinthians with his world cup winner’s medal and a whole host of new fans.

At Corinthians he was treated as a hero – The Little King — and was the shinning jewel in the team. Unfortunately, the rest of the team were not remotely of the same standard and in his time with the club he won nothing whatsoever.

Despite their star midfielder, Corinthians were not a good team and when they lost a state final in 1974 to their great rivals, Palmeiras, and in a country fuelled full of superstitions, Rivellino was blamed for being some kind of hoodoo or unlucky charm.

After that losing final and a nine year stay at the club, he walked out of the ground with his coat turned up and never returned to the park where he had been king.

In the interim, he was a stalwart of the new Brazilian team which now had to move on after the retiral of the great Pele and others.

It is said that Rivellino is singlehandedly responsible for dragging a pretty dreadful Brazil to a creditable fourth place in the 1974 world cup.

The 1974 national team were nothing like the team of 1970. Jairzinho was still there but he was no longer the fast strong hurricane of a player from 4 years before and the players around him were not of the same calibre as the heady days of Mexico.

However, Rivellino was there and now he was in the middle of the park and not confined to the left hand side. Once again he scored three goals in the finals – enough to make him his country’s top scorer in the tournament.

Just as he was at Corinthians, in the 1974 World Cup finals he was seen as almost a one man team.

He pomped and preened his way through the tournament with some majestic football that was awe inspiring. In the intervening years he had helped Brazil to some memorable victories in South America in minor tournaments and friendlies, but at the really top level his country was found wanting and in particular their tactics were seen as far too negative and counter attacking which didn’t suit the style of football that Rivellino had come to represent.

There was a new dawn in world football and the Brazilians would lose out in the semi-finals to Johan Cruyff’s wonderful Dutch team despite Rivellino himself being excellent. They would also lose the third place play-off game to Poland who were the surprise team of the tournament.

However, it was widely accepted that Riva was the midfielder of the tournament.

In 1974, whilst still at Corinthians, Rivellino would score a goal that was described as “the miracle goal” in the Brazilian press. The goal was not, of course, a miracle but did show the combination of quick thinking, tactical astuteness, skill and vision for which Rivellino had become known in his home land.

As he and a Corinthians team mate kicked off the start of the match, Rivellino noticed that the opposition goalkeeper was otherwise engaged. Some reports say that the goalkeeper was praying, others say that he was speaking to a photographer at the side of the goal just as the game commenced. Either way, Roberto Rivellino noticed that the keeper was not paying attention and upon receiving the ball from the kick-off he thundered the ball towards the goal from behind the half way line with a swing of his mighty left foot.

He was never officially awarded the accolade of the fastest goal in history as there was simply no means of recording the feat at the time but some reports say that the ball struck the net in less than three seconds from the sound of the first whistle. All that is known is that the goalkeeper did not know that the shot had even been struck and that his first knowledge of the game being underway was when he was alerted to the fact that the ball was in the back of the net.

In Brazil, and South America generally, the goal took Rivellino’s reputation to a new level, and it perhaps explains another phenomenon that was to occur not long after.

When he lost in the state final with Corinthians, Rivellino left the ground of the club he had served for over 9 years without knowing that he would never return as a Corinthians player.

The next he knew was that he was being sold to Fluminense who played in Rio De Janeiro and where he would have the most spectacular effect even before he had kicked a football.

In Rio, carnival is king and when Mardi Gras time comes the football stadiums lie empty as nothing can compete with “Carnival”.

However, his new employers decided that Rivellino would make his debut for Fluminense at the Maracanã on the first Saturday of carnival. The game concerned was a friendly against Corinthians and was no doubt part of the transfer deal between the two clubs. To play a pretty meaningless friendly on the Saturday of Mardi Gras was a decision which was widely thought of as crazy, but nonetheless that was when the game was scheduled to be played. It was widely thought that no one would come to watch.

Amazingly, over 100,000 spectators came to the game that day. This was so completely unusual that it was worthy of comment on the national news and when offering an explanation as to why so many people had gone to a football match on a day when nobody goes to see a game, the pundits were unanimous in their explanation – Rio de Janeiro had turned out to see Roberto Rivellino!

And what a show they were given?

Playing against the club which had so recently released him, the moustachioed midfielder put on a masterclass for the benefit of those watching and scored a spectacular hatrick in the process.

Now, Rivellino would get his winners medals. Playing in a team that boasted players in every position who were either current Brazilian internationals or who had been Brazilian internationals, Rivellino’s Fluminense would win titles, cups, and trophies by the bucketful.

Over the next few years, Roberto Rivellino virtually held a weekly masterclass in midfield football.

His Fluminense team waltzed past opponents with such relentlessness that in a country where giving someone or something a nickname is second nature they were deemed “A Macquina Tricolore” – The Tri Coloured Machine.

The line-up for this team – deemed one of the greatest if not the greatest Brazilian club sides of all time included Felix in goal, fullbacks Marco Antonio and Carlos Alberto, Edinho, Neto, Paulo César, Dirceu, Gil, Doval and various others who would all command International recognition.

Rivellino was not so much the engine room of that machine but more the rhythm section of a truly sensational band, and he himself was the chief soloist.

The passing, the ball skills, the close control technique were all on show at their best as he teased, dominated, conducted, dictated and orchestrated his team mates and the game in general.

He won two state championships back to back and collected numerous other trophies with Fluminense prompting one former International team mate to comment that in that period he collected more trophies than any one man could carry.

The victories at that time included what was billed as a game between the two greatest club sides in the world with the Brazilians facing a Bayern Munich side which boasted Beckenbaur, Muller, Hoeness, Rummenigge and all the others who made Bayern top dogs in Europe.

The game resulted in a 1-0 victory for the Brazilian side with Gerd Muller scoring an own goal when trying to track back to cover a Fluminense attack. However, the ball only hit the back of the net after Rivellino had “flipped flapped” Beckenbaur and the rest of the defence and played a superb ball through for a team mate which would undoubtedly have resulted in a goal anyway had Muller not stuck out a foot.

In Brazil it was reported that the 1-0 result did not reflect the true nature of the game and that Fluminense were so dominant that they could have clearly won by 4 or 5 goals or even more.

In talking about his time at Fluminense, Edinho describes Rivellino as just sensational in their midfield. The range of passes, the ability to read the game, the spectacular goals and the tricks, flips and flaps were all on show and had the crowd on their feet week after week.

Fluminense toured Europe and won an invitation only tournament in Paris where they defeated Paris St Germain with two goals from Rivellino and then went on to defeat a European team which was made up of various stars from across the continent.

The French press declared Rivellino as the greatest player in the world at the time.

Ironically, in Fluminense’s second great year, 1976, their manager was Mario Travaglini who had told the young Rivellino that he would not be offered a contract at Palmeiras all those years before.

On the international front, 1976 saw Brazil invited to play in a 4 team competition in the United States as part of that countries bi – centennial celebrations. Besides Brazil, the other teams to play were England, Italy and an American league team made up of players from many countries who were now playing “soccer” in the USA. This team included Pele, Giorgio Chinaglia and Bobby Moore among others.

Both England and Italy were at full strength while there were two notable features about the Brazil team.

The first was that they had a new Captain in Roberto Rivellino and the second was that Rivellino himself had a new young, raw, skinny, long haired midfield partner called Artur Antunes Coimbra. To avoid confusion within his family where there were a few “Arturs”, this young Artur was given a family nickname “Arturzico” and this nickname was then further shortened to Zico.

The American league team were not up to much and so the competition came down to Brazil, England and Italy. Indeed, at the end of the game one of the English born players playing in the American team, a chap called Eddy Keith, was so star struck at playing on the same park as the Brazilian captain he ran the full length of the park to try and swap shirts with Rivellino only to find the little king of the park exchanging shirts with Bobby Moore!

The Italian team which faced Brazil was very strong with a starting line-up of Zoff, Facchetti, Bellugi, Benetti, Antognoni, Tardelli, Capello, Causio, Graziani, Pulici and Rocca. Later they would bring on Roberto Bettiga and Eraldo Pecci among others.

Brazil, fielded a slightly experimental side featuring the midfield trio of the wily old Rivellino surrounded by the younger pairing of the attacking Zico and the more defensive Falcao.

Fabio Capello opened the scoring for Italy but the Italians eventually succumbed to a 4-1 defeat which could have been more.

Zico scored a great goal from midfield after Gil had scored two excellent goals stemming from superb Rivellino passes, and the big Brazilian forward Roberto added a fourth.

However, there is a video piece on you tube which shows the performance of Roberto Rivellino in this game that is worth the watching, principally for Riva’s passing exhibition against a very good Italian midfield, but also for the fun of watching world class footballers become so frustrated with his posing, strutting and general micky taking that they resort to pure unadulterated physical violence of the crudest kind.

Rivellino himself is shown as no soft touch, but his swagger and deliberate tormenting of the Italian midfield is something to behold.

The first Brazilian goal in this game comes from a Rivellino pass which almost defies belief as he sends the ball fully fifty yards through the heart of the pitch. The ball seems to bend first one way and then the other cutting out five Italian players before landing at his team mate’s feet in the penalty box.

However such a pass was apparently common place for Roberto Rivellino and his side went on to defeat England and the American league team to lift the trophy.

Rivellino was still playing international football in 1978 and featured in the world cup qualifying campaign and friendly matches in the lead up to the world cup finals in Argentina.

While he did travel with Brazil to the 1978 world cup, he did not feature much as he was carrying an injury and it is a world cup the great man does not remember with relish despite playing very well in the third place play-off game.

However, a relatively poor Brazil did succeed in coming third in Argentina though back in Rio the very thought of Argentina getting their hands on the new World Cup trophy was enough to cause great public angst and the 1978 finals marked a need for change of thinking within the Brazilian FA.

As a player on the international stage, Rivellino’s time had come and gone, however in many respects his noticeable long lasting influence was only just beginning. The great, but ultimately unsuccessful, Brazil side of 1982 would have more than a touch of Rivellino’s flair and swagger about them which is not surprising as most of that team had grown up watching the side of 1970 and had been inspired by the beautiful football it played.

I had sat and watched the 1970 World Cup on the television in glorious Technicolor like millions of other spectators. As has been mentioned above, few Europeans knew anything about Brazil other than that the great Pele played for the country, but beyond that they could have been a one man team as far as a European public was concerned.

Whilst the whole team impressed and Pele’s iconic smile became ever more famous, it was the “other” Brazilian players who were somehow a surprise.

The powerful and tricky Jairzinho ended up top scorer with a goal in every game. Tostao and Gerson were heralded for their clever contributions and Carlos Alberto scored the greatest world cup goal of all time.

However, Rivellino’s moustache, trickery, craziness, passing, creativity and his shooting prowess made him a viewer’s favourite and not just in in Europe either. As Harry Redknapp would later point out, the greatest coaching vehicle in the world for anyone – particularly kids – is to see great players doing what they do, and just as Johann Cruyff would 4 years later, Rivellino lit up the world cup with his ball tricks, step overs and elastico fantasticos firing the imagination of kids and adults all over the world.

Thousands of ten year olds like me were glued to the TV back in South America and one in particular is in no doubt what and who was most memorable and inspirational. Many years later he would recall the 1970 world cup with these words:

‘When I was a kid I used to watch Brazil play. I wasn’t bothered about what Pele was doing, though. I used to watch out for Rivellino, on the other side of the pitch. He was everything I wanted to be as a player. His dribbling was flawless, his passes perfect and his shots unstoppable. And he did everything with his left foot. It didn’t matter if his right foot was only good to stand on, because there was nothing he couldn’t do with his left. To me it was beautiful. He was my idol.’

To be fair, Rivellino’s right foot was for more than standing up in, as in the 1970 final against Italy it was with his right foot that he thundered a shot off the bar and you only have to see his right foot volley against Botafogo while playing for Fluminense to realise that it was no mean footballing weapon in its own right.

However, the kid who watched back then only saw a stocky left footed guy who could do everything with that left – run, dribble, tackle, pass, shoot and control the game despite being below average height and with apparently just the one foot.

The kid was called Diego Maradona and he has since repeatedly made it clear that Roberto Rivellino was the footballer that he always wanted to be!

From the mid 70’s onwards, South America produced a succession of midfielders who all pay homage to the football of the one and only “Riva”.

Osvaldo Ardilles, Socrates, Maradona, Zico, Kaka, Ronaldinho, Juninho, Rivaldo, Riquelme, Carlos Valderrama and many more in between and since, all eventually talk about what they saw in Roberto Rivellino that made them want to be the footballers they became. Strikers such as Romario and Ronaldo also talk of Rivellino as an inspiration in terms of ball control and shooting for goal.

Ronaldinho in particular liked the Rivellino style of play. “I used to dream of being Roberto Rivellino” he says. “I would watch endless videos of him and wanted to be left footed like him, do tricks like him. He was, and still is, one of my greatest idols and heroes.”

The use of the elastico fantastico was taken to a new level by the tall and muscular Brazilian between his time at PSG and at Barcelona where he used the move at spectacular speed and with devastating effect.

As has been pointed out, today, Cristiano Ronaldo, Neymar and of course Lionel Messi all use moves and dribbles that many first saw with Rivellino and which were later passed on by many others like Zico, Socrates and Maradona.

However, the comparisons do not stop there because as Pele said one of Rivellino’s greatest talents was his tactical awareness, his discipline and his ability to control the game and see where it is going.

Whilst it was not evident in the 1970 world cup where he was deployed more on the left wing, in his more central role in later years – particularly when with Fluminense – Rivellino became the rhythm section of his team by conducting a series of short sharp passes in seemingly tight areas of the pitch while surrounded by opponents. It was something he learned on the streets of Sao Paulo.

He would get the ball, give it, get it back and give it again whilst all the time controlling the direction of the play and the fate of the football, knocking it about with spin, slice and pace like a golfer with a wedge or a tennis player with a tennis racquet.

The pattern of play adopted by Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona and by Messrs Xavi and Iniesta in particular can find their pure roots in the footballing brain and instinctive style of play of Roberto Rivellino.

An adaptation of that passing style of play and the constant movement into space was a key part of the total football system so advocated by Rinus Michaels and performed brilliantly by Johan Cruyff. Cruyff would later take the “system” to Barcelona and instil it into their training regimes with the youth teams in particular being trained to run into space to receive the ball and then give it back.

Roberto Rivellino would openly say of the Dutch World Cup team that they brought a new style of football to the tournament and that they had to be admired for that.

However, 4 years before the Dutch entertained the world with their system, Roberto Rivellino, as an individual, was playing football in exactly the same way having learned the same lesson on the streets of Sao Paulo and using his footballing instinct and unbelievable skills. Get it, pass it, move and get it again and repeat.

One footballing article I have read suggests that Rivellino was the most influential South American footballer of his generation and perhaps of the past 50 years! And it cannot be denied that the influence of South American players on European Football has grown increasingly since the 1978 World Cup with ball players and entertainers becoming real supertsars within the game.

When his days at Fluminense had come to an end, his old International boss, Mario Zagallo, signed him for a club he was managing in Saudi Arabia and it was there that Rivellino saw out his professional career.

He was still scoring spectacular goals, and making the crowds gasp with his skill and artistry but the fitness was going and his time on the pitch was coming to an end. However, the goals and the tricks were in evidence in abundance and as the standard of player he played against dropped in comparison to World cups and the Brazilian domestic league, so Rivellino would conjure up ever more fantastic feats in Saudi Arabia.

In the course of winning three successive league titles there, he would score free kicks from forty yards out, play sublime passes and generally flip flapped and back heeled to the cheers of the crowd who came to watch in their thousands.

In South America, in particular, the Rivellino legend shows no sign of diminishing. In January 2015 the Argentinian midfielder Juan Ramon Riquelme announced that he was retiring from football after a stellar career.

There is no doubt that Riquelme was a terrific footballer and given that he was a gifted midfielder comparisons to others from the past were inevitable.

One such comparison was with Rivellino and stated that the Brazilian was the left footed or “southpaw” equivalent of the right footed Argentinian Riquelme.

The reaction from some was very heated and immediate. While most admired the talented Riquelme many did not think he was worthy of comparison at all to Rivellino stating that it was like comparing Monday to Friday. They are both days of the week but at different ends of the spectrum and that the very comparison was an insult to Rivellino.

“Riquelme is a great player, but it’s not fair to compare him to the genius that was Roberto Rivellino” said one critic with another adding unkindly that the only comparison that could be made would be to say that Riquelme was an overrated midfielder compared to Rivellino simply being an underrated genius!

The point is that almost 50 years on, In South America no matter how good you are you are not likely to outshine the reputation of Roberto Rivellino.

When he eventually retired and returned to Brazil “Riva” bought a petrol station but had to give that up because his ownership caused endless traffic jams. Motorists would queue for hours to get petrol just in the hope that their tank would be filled up by the great man and they could catch a few words.

However, his great love was always football and he never forgot the days when he was dirt poor and when he and his friends had to play with no shoes, no socks and no ball.

In due course, he was persuaded to write his autobiography, the title of which said everything about his entire philosophy on football, what was most important in his football career and perhaps about life in general

It was called simply “Get out of the street Roberto!” and is a reference to the regular call that came every night from his mother when trying to persuade her son to come into the house and stop playing football. In it he states categorically that “… the streets formed me as a man and a footballer” and that his entire being, all his success and his attitude to life in general was shaped by the experiences of his childhood on the streets of Sao Paulo.

This belief and overriding attitude also explains why he built the Roberto Rivellino soccer school for children right in the middle of his native city, one of the most densely populated cities on earth. Barely a square foot of the city is not built upon and developed, yet today, in the heart of an ever growing concrete jungle, there are some football pitches ( grass and Astroturf ) which bear the great man’s name and where kids can come and learn their football skills under the tutelage of Rivellino approved coaches and sessions.

He is adamant that the ever continuing development of the cities of Brazil have ignored the “street education of children” leading to a reduction in the amount of street football and a consequential deterioration in the ball skills among the young men and women of today. The result, he argues, is that Brazil now produces far fewer footballers with real natural talent, and he passionately rails against such a situation. He further argues that if older guys like him gained raw basic skills in unorganised games played in urban open spaces and then progressed to provide the beautiful football of the 1970 World Cup team, then why can’t that lesson be replicated and maintained throughout Brazil ( and the rest of the world ) rather than be allowed to die under the auspices of so called progressive inner city development?

Today, as he heads towards his 70’s, he is a regular TV pundit on football and he hosted one famous show with Maradona where they talked football, football and football.

He owns the bar mentioned at the start of this piece and is treated by the public as an iconic godfather like figure with people coming to visit him virtually all the time.

In 1989 he came out of retirement and helped a seniors Brazil side to the title of World Cup of Masters where he scored in the final against Uruguay thus becoming the first player in history to have won the world cup and the senior’s world cup.

He is not averse to being commercial and knows what he is worth in terms of media contracts, yet at the same time the small balding paunchy man is neither a big head nor a braggart and as mentioned above he is a street footballing socialist.

His name appears regularly in polls of “the greatest” conducted by football magazines, UEFA, FIFA, retired players and sports journalists with monotonous regularity and for all sorts of different skills.

He has been voted as one of the greatest number tens of all time and is mentioned in the same breath as Pele, Platini, Zidane, Puskas, Maradona, Baggio, Hagi, Messi and Matthaus and at one point was voted as the fourth greatest footballer ever to come out of Brazil behind Pele, Garrincha ( his own personal favourite ) and the aforementioned Zico to whom he taught a thing or two .

He makes the list of the top 100 or 50 footballers of all time on a repeated basis despite the fact that more modern players get far more exposure and media coverage and so their feats and skills are more readily available to watch on video.

When Geoff Hurst chose his top 50 players of all time he added that in his opinion Rivellino, Pele, Jairzinho, Gerson and Carlos Alberto would have formed the greatest 5 a side team in history and would probably have beaten many 11 a side teams without a goalkeeper! By the way Gerson and Carlos Alberto didn’t make his list.

Rivellino is the only player listed as scoring two of the top 25 free kicks of all time. His goal against East Germany in the 1974 world Cup has to be watched in slow motion to be believed and to fully appreciate its pace and accuracy. Michel Platini has described that goal as firing the ball through a mousehole!

The name Rivelino appears yet again in the list of players who were the all-time great dribblers with the football with many citing him as a supreme example of someone who had complete control of the football with his step overs, flip flaps, feints and dummies.

When it comes to who had the hardest shot he is always nominated, as he is when it comes to the most stylish player ever seen, the player with the best left foot, the player with the best tricks in football, and of course the player with the most memorable moustache!

In some articles his football is described as “art” or “sheer artistry with a football”.

Any discussion about who was the best passer of the ball results in the name Rivellino once again coming to the fore, and those who played against him remember some of his passes with awe. The one mentioned above in the 1976 game against Italy in America was one such pass, however another is graphically described by Kevin Keegan in his autobiography where he makes no attempt to hide just what he saw and felt when playing against Rivellino.

“I’ll never forget one of his (Rivellino’s) passes in Rio, it was every inch of 80 yards,” wrote Keegan in his excellent 1979 book, Against The World. “I wouldn’t have believed it was possible to strike a ball so hard, so far, so accurately, until I saw Rivellino do it from the edge of his penalty area.

“The target man was 20-yards inside England’s half and starting a full diagonal sprint to get behind Dave Watson and Emlyn Hughes. Yet the ball pinpointed him, it fell in his stride. He didn’t need to change direction. I was about three yards away from Rivellino and I felt the wind as the ball passed me at shoulder height. The astonishing thing is that it stayed at the same height all the way. I watched wide-eyed as it flew on and on; that’s one of the rare times when I’ve felt outclassed.”

Yet that very pass throws up two conundrums about assessing Rivellino’s place in the record books of world football.

The pass was never caught on TV. Many of his truly great performances are only reported by eye witnesses while the skills of others he is compared to and with, and who played in a later era can be seen time and time again and so help further their reputation.

With Rivellino you have to go with the younger stars who went on to play for Brazil, Argentina and whoever at a later date to truly measure his impact, and you have to rely on guys like Keegan and Beckenbaur who played against him, and others like Pele, who played with him, to really get a sense of how highly players of real calibre rated him.

Keegan’s report of the pass in Rio raises another issue and takes you back to Pele’s comments about Rivellino’s intelligence as a footballer. His vision was said to be legendary and that he could see where the game was going long before others could. He could see where players were and where they could and would move to.

And so the question has to be asked when considering the pass described by Kevin Keegan: Did the forward player start to make the diagonal run which Rivellino then responded to instantly and with great skill in a split second, or did Rivellino strike the pass into an exact spot causing his colleague to make such a run thus changing the pattern of the game?

Pele says that Rivellino could do both. He could react with such skill that he made the ball do all the work whether the pass be short or 80 yards long, and he could play the ball in and into areas which would instinctively make players, both team mates and opponents, move into areas where they had no intention of going only seconds before.

Rivellino will never be heralded as the greatest overall player in the world, nor the greatest in any one discipline or skill to be seen on the football pitch.

However, what is clear is that to be classed as a better overall footballer than he was, or even his equal, in any area of the game, you had to be truly exceptional in any era and come from that rare pantheon of footballers whose legend transcends the generations and more importantly inspires others.

Those who do the voting and saw him play in the flesh care not for the comparison to the later Rivellino-likes no matter how good they may be or may have been. He was the original. He was the one little king of the park playing with a heavier ball and they will tolerate no mention of any pretender. He was the originator of moves, tricks and dribbles. Others may have taken those moves on, perfected them with the lighter ball which is easier to move and bend and deployed them before a greater TV audience, but they were not the original.

He has been dubbed “Maradona’s professor” and was the footballer who inspired not only the average Joe in the crowd but also a host of kids and young men who would go on to rank as among the greatest footballers the planet has ever seen. In that sense his influence can still be seen on the field of play to this day.

Some may argue that others like Cruyff were more influential, were better and more effective players and have had a greater lasting effect on the game.

However, Cruyff and others, whilst undoubtedly brilliant, played in a system, were coached and taught many aspects of the game with the result that the teams they played in were dominant for a period until someone else worked out a tactical solution to combat their system.

Rivellino’s skills on the other hand were natural, learned on the street, and then adapted and used in the professional game. He was not always surrounded by great players or deployed in a team which played to a winning system, but he still stood out and made the game seem magical.

He made kids want to play football like him and there can be no greater compliment especially when you consider the number and the calibre of players who would later say they were Rivellino inspired.

Zico would play for his country 71 times; Gerson would amass 70 caps as would Romario. Kaka gained 87 caps, Jairzinho 81 and Rivaldo 74. Carlos Alberto turned out for Brazil 53 times and the legendary Garrincha would make 50 appearances. Cruyff would only play 48 times for Holland.

Rivellino would make exactly the same number of official international appearances as Pele with 92 caps, though some lists credit Rivellino as having appeared 96 times as some games were not treated as official Internationals.

Either way, he played for his country more often than Falcao and Socrates put together as they amassed 28 and 60 appearances respectively.

Had Saldanho not frozen him out over a thirteen match period then he may well now be classed as the third highest capped player in Brazilian history behind Cafu and Roberto Carlos neither of whom, while good, were the same calibre of footballer. He would also have added to his tally of 26 International goals.

When it comes to the measure of putting bums on seats, it is arguable that Rivellino was in a league of his own with his trickery, his shooting, his celebrations and his overall pomp, flair and character. Millions all over the world tried to copy his moves in training grounds and playgrounds and his very presence was guaranteed to add to the number of spectators attending any match. In the days before global football coverage on TV, Roberto Rivellino singlehandedly increased the gates at every club he ever played for.

One commentator has remarked that he came to watch Fluminense at the age of 14 and to see Roberto Rivellino play in that first match on the Saturday of Carnival. The same man goes on to say that he was so thrilled while Rivellino remained at Fluminense he never missed a single match.

Other than his final stint in Saudi Arabia, he never played football for any club outside of his native Brazil. His was an era when South Americans generally did not travel to Europe.

However, had the market for Galacticos been in existence in his era, there can be no doubt that the Real Madrid’s, Barcelona’s and the likes would have broken the bank for Roberto Rivellino.

Yet at no time in his career did he seek a move. He simply played and spent the majority of his career playing for a provincial side that were not very good while at the same time developing a reputation as a truly special footballer.

Unlike the little King of the Park, many of the later players who were inspired by him, and who would emulate his talents and tricks, only did so in the most talented of winning sides whilst earning millions of Pounds or Euros.

It could be argued that Rivellino was among the last of the truly great provincial players as from the 1978 World Cup onwards football players became real global stars with money dictating that the entertainers and ball players who would put bums on seats would cross oceans to play in successful teams.

Zico would go to Italy, Ardilles to England and Kempes to Spain thus heralding the fact that in due course the real ball players, the trick masters, the exceptional footballing talents would always command the highest transfer fees and go to the biggest clubs – and most would cite Roberto Rivellino as either their main influence or one of their main influences.

Yet the man himself is somewhat humble. He is or was a footballer and simply loved being one. He is a critic of the modern trend towards tactically killing the game and bemoans the lack of genuine skill and flair in the modern footballer.